Economic Diversification in Nigeria. Why Context Matters?

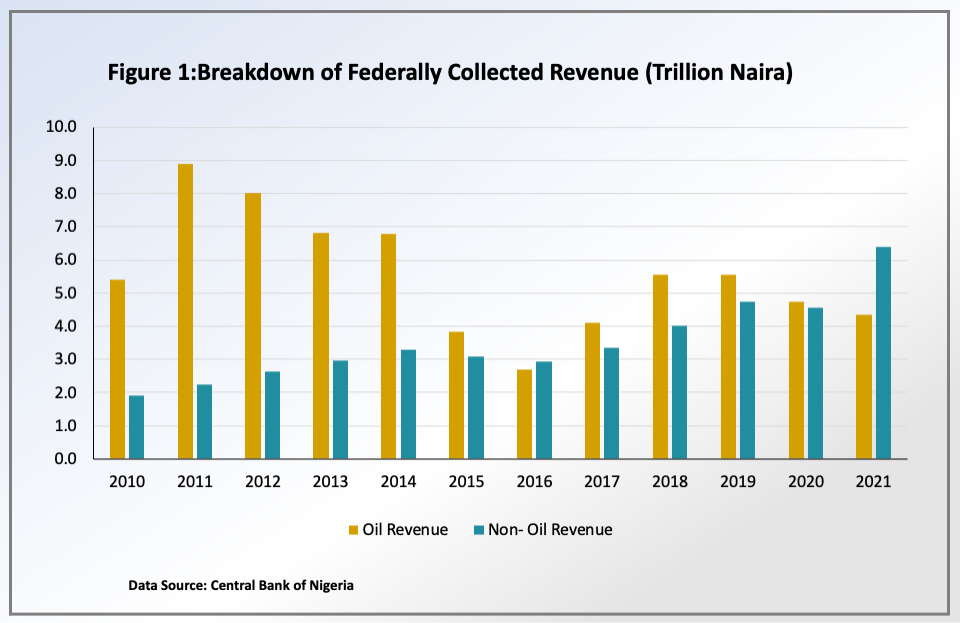

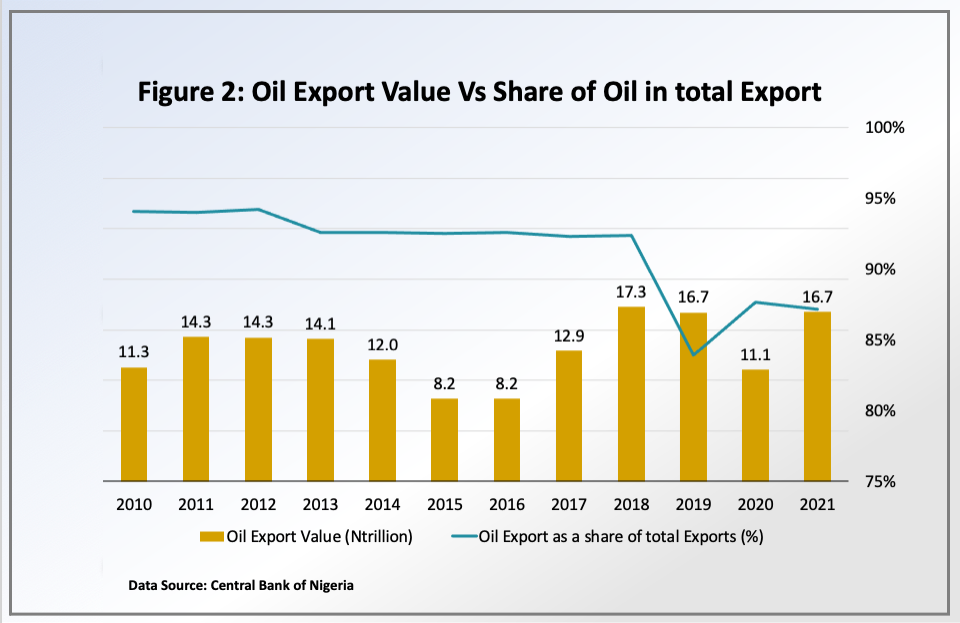

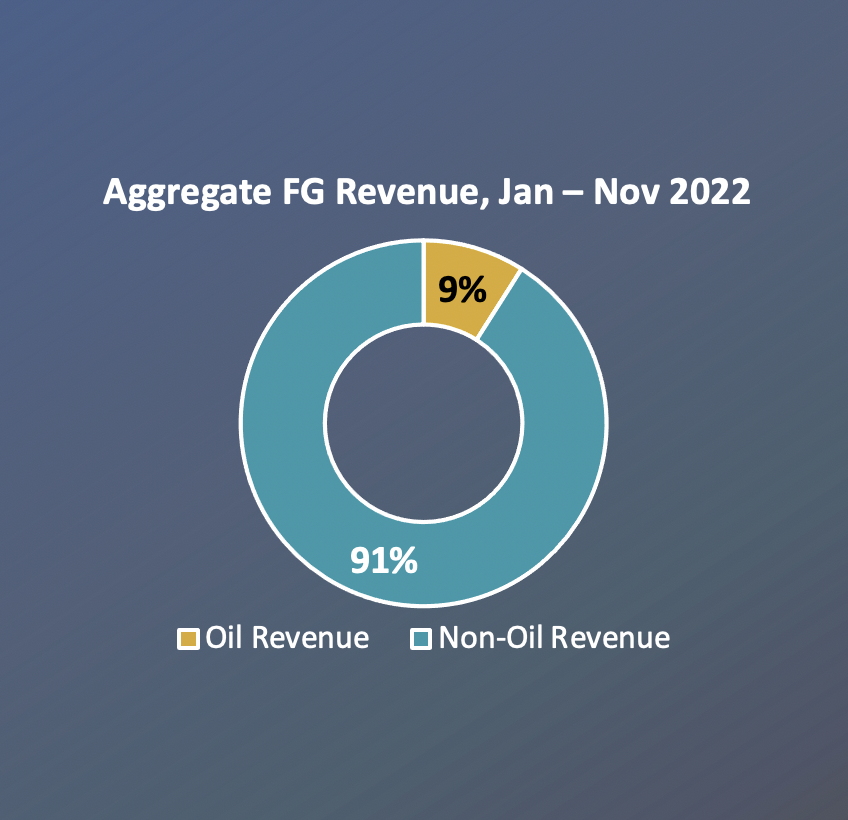

Nigeria has a complex relationship with crude oil. Back in the 2000s, the average share of crude oil in Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 23% and its average share in government revenue was 80%. As regards exports, oil accounted for 99% of total export earnings in the year 2000, according to data from the Central Bank of Nigeria. More recent data on oil’s contribution to the economy show a declining trend. The oil sector accounted for as low as 5.7% of GDP in the third quarter of 2022 and its share of total revenue was also low at 9% from January to November 2022.

For exports, oil’s share is still high at 91% in 2022 (Jan-Sept), however, its share has been declining. One reason why oil exports still has a high contribution to overall export is that export data in Nigeria only capture export of goods. It does not include services export, unlike GDP and revenue data. If data on export of services become available, the share of oil export in total export will be lower.

From the above narrative, it is clear that crude oil is not as important as it used to be to the Nigerian economy; although it is still important. The point here is that the level of significance (not in statistical terms) crude oil has on the economy is declining. Given the low contribution of crude oil to GDP and revenue as shown above, some political and economic leaders have stated that the Nigerian economy is now diversified; but is this the kind of diversification that we should celebrate?

Understanding the Context of Diversification

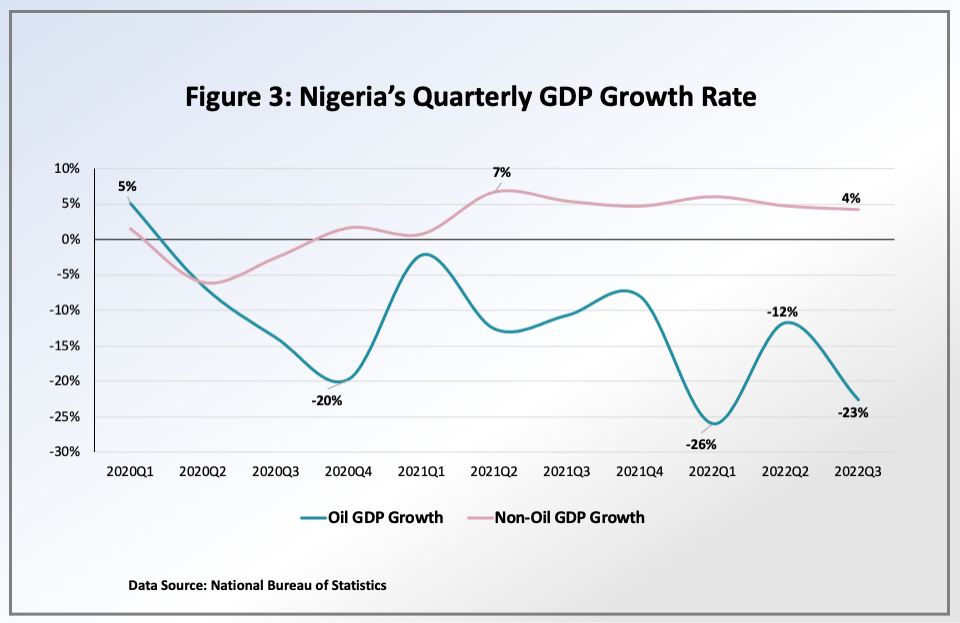

Diversification, like any economic phenomenon, must be discussed in context. It has to do with shares or contribution of sectors to the economy whether in terms of output, revenue, employment and export. Because diversification deals with shares, once the value of say, sector A, decreases, the share of the sector B automatically increases, provided that the value of sector B remains the same, increases or falls marginally, relative to sector A. Now, my argument is simple: the kind of diversification that Nigeria needs is one that increases the actual value of both the oil and the non-oil sectors, but where that of the non-oil sector rises rapidly and faster than that of the oil sector. In such instance, the share of a sector may decline, but its value is increasing. This is the exact opposite of what we find in Nigeria’s so-called diversification narrative especially when it comes to revenue, as oil revenue accounted for 9% of total revenue in 2022. Actually, what is happening is that the value of Nigeria’s oil sector/revenue has been shrinking. Just looking at the share, it is easy to argue that the economy is diversified, but this argument does not tell the full story behind the falling share of oil revenue.

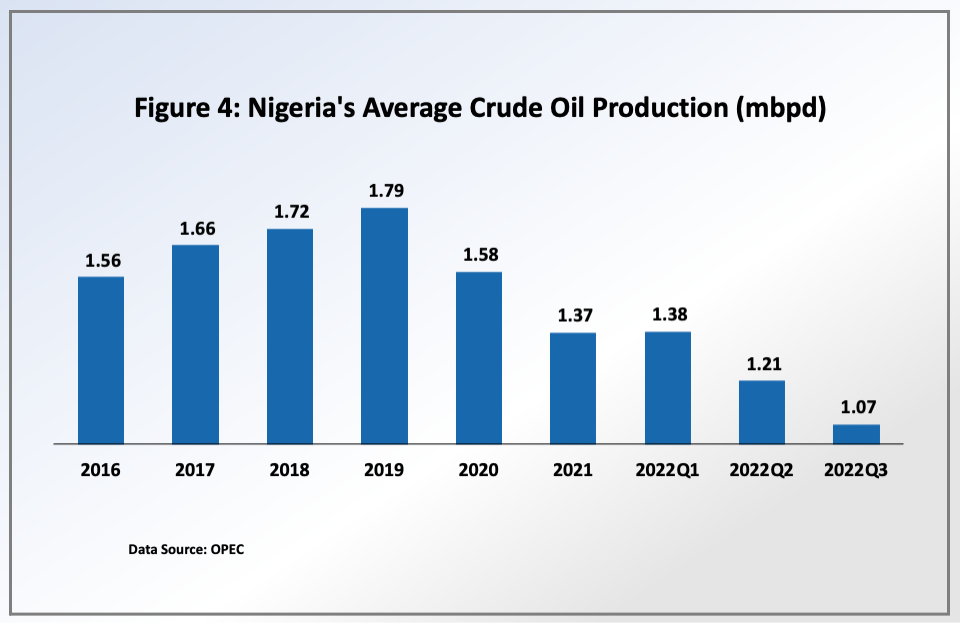

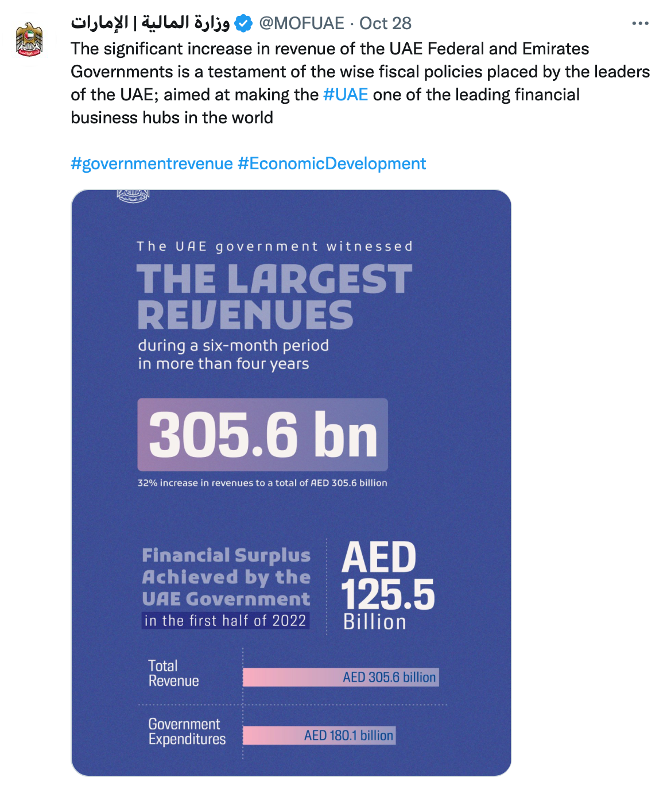

One of the main drivers of the declining oil sector in recent years has been lower oil production caused mainly by oil theft. OPEC figures showed that Nigeria produced an average of 1.16 million barrels per day (mbpd) in November 2022, far below its quota of 1.826 mbpd. Nigeria’s oil production trended downwards for the most part of 2022. The interesting but sad tale is that within this period, oil prices trended upwards above $100 per barrel due to the war in Ukraine. Other oil producing countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) leveraged higher oil price to improve their reserves and revenue. For the first time in more than four years, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) experienced a significant increase in revenue in the first half of 2022 and achieved a financial surplus of AED125.5 billion. Saudi Arabia reported a budget surplus of $40bn in the first 9 months of 2022. But in Nigeria, we are embracing a so-called economic diversification which is simply driven by the fact that our crude oil is being stolen?

The narrative of this so-called diversification can be misleading for several reasons. First, we may be tempted to think the economy is now resilient when in actual fact, macroeconomic instability is heightening. What we find with this so-called diversification narrative is that the value of Nigeria’s oil sector is shrinking. In fact, Nigeria’s crude oil sector has been in recession since the second quarter of 2020 i.e. the real value of the crude oil sector has fallen for 10 consecutive quarters (from 2020Q2 to 2022Q3). This also means that the oil sector is weighing down overall GDP growth. If the sector had not been in recession, real GDP growth of the Nigerian economy would have been higher in the last 10 quarters, thereby, raising confidence level on the economy. In addition, improved oil output would have raised revenue prospects for the government, limited debt accumulation and led to the growth of external reserves. Recently, the CBN governor was quoted as saying “the official foreign exchange receipt from crude oil sales into our official reserves has dried up steadily from above US$3.0 billion monthly in 2014 to an absolute zero dollars today”. This shows an estimate of how much Nigeria has lost as a result of oil theft; and how many Nigerians have been pushed into poverty following the depreciating exchange rate and the attendant high inflation caused partly by weak dollar inflows.

Second, this wrong narrative of diversification is important in policy analysis. It could inform a neglect of the oil economy, especially in view of the global narrative of the transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. But whether we like it or not, oil, and by extension, gas, will continue to power the global economy in the next 5-10 years, at least. Gas is what powers the European economy and Nigeria’s gas is largely unexplored. As several oil producing countries are doing, we must work to attract private investments into the sector. We need to maximise the benefits in the oil and gas market, at least now that these commodities are still, and will still be relevant, in the next decade. Take for instance the United States, the country with the largest economy in the world. It is also the world’s largest oil producer, ahead of Saudi Arabia. Oil production in the US has been on the rise since 2020 and it stood at 12 mbpd as at August 2022. Similarly, in January 2023, Norway awarded 47 new offshore oil and gas exploration licences to 25 oil companies to maintain the production of oil and gas and ensure “that Norway remains a safe and predictable supplier of oil and gas to Europe”1. These show that even countries in the global north are scaling up oil production to meet the needs of both the local and global markets.

Back to the case of Nigeria. Understanding the dynamics of sectors in the economy is important in ensuring effective diversification. The oil sector is not important for massive job creation due to its capital-intensive nature. However, the sector can provide the funds needed to ensure macroeconomic stability and economic resilience through external reserve accretion, exchange rate stability, and revenue growth, all of which are important in ensuring the growth of the non-oil sector, especially the manufacturing sector. One critical lesson from COVID-19 is that having large foreign reserves and fiscal savings, whether the country is oil-rich or not, is important in ensuring economic resilience and in supporting the poor and vulnerable in a society. At the height of the pandemic, many countries that built large savings were able to quickly intervene to support households and businesses without significantly accumulating huge public debts or seeking for bailouts. Diversification is important in building economic resilience and limiting vulnerability to external factors, but so is fiscal savings of the proceeds from crude oil sales.

The discussion of economic diversification cannot be complete without making reference to the manufacturing sector. Ultimately, a rapid expansion of Nigeria’s manufacturing sector both in terms of output and exports is what will create jobs, raise income level and ensure sustainable growth of the economy over time. Sadly, this sector has been severely challenged in Nigeria. According to NBS data for full year 2021, the share of the manufacturing sector in total real GDP and exports earnings stood at 9% and 5.2% respectively. Latest NBS figures for 2022Q3, showed the respective shares at 8.6% and 2.2%. When we compare manufactured goods exports and manufacturing output, the scale of the problem in the sector is magnified. The share of manufacturing output that Nigeria exports was only 4% in 2021 and 2% in the first three quarters of 2022. We cannot build a strong, resilient and competitive economy with such GDP and export structure. Nigeria needs to reconsider the introduction and implementation of industrial policy to provide coordination, targeted infrastructure and attract private capital into key areas of the manufacturing sector. This must be executed in view of the opportunities associated with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement.

While we must actively pursue the expansion of this crucial sector, in my view, this should not be done at the expense of the oil & gas sector, especially given the fact that the major cause of the decline of Nigeria’s oil sector, in recent times, is not due to external factors that are beyond our control. It is as a result of oil theft, negligence and several other factors. Oil theft has made a few individuals richer at the expense of the populace. It has resulted in revenue losses for the government and is part of the reasons for massive debt accumulation. Its impact on foreign exchange and external reserves are also glaring. If macroeconomic stability and, by extension, the economy is a priority for the government, such menace should not have been allowed to continue for this long. It needs to be treated as a matter of national emergency by both the current and incoming administration.

Finally, I should say that many Nigerians have been sold a narrative that the economy is where it is today because of crude oil. Some economists and analysts have argued in support of the resource curse hypothesis. But the fact is this – the problem with the Nigerian economy is not the commodity, because there are countries, whose realities, negate the resource curse argument. The UAE’s creation of Dubai as a major tourism and trade hub is just one example of how oil revenues can spur development in the non-oil sector, provided there is sound economic and institutional management.

Particularly for Nigeria, we have (1) failed to significantly grow crude oil revenues even when oil prices are high (2) failed to save for the rainy day and (3) failed to use available crude oil revenue to develop critical areas of the economy, as some oil producing countries did or are doing. At the moment, Nigeria is failing to get enough revenue from oil and gas. Crude oil is no longer as important as it used to be for Nigeria and Nigeria keeps losing its relevance in the global oil market. This is not something that we should celebrate, especially because our non-oil sector is not growing fast enough to cover the budget and trade shortfalls, due to a large informal sector and lower productivity, occasioned by a challenging business environment.

Notes

- Data used in this article are from the 2021 Central Bank of Nigeria Statistical Bulletins; Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) GDP Report 2022Q3; NBS Foreign Trade Report 2022Q3; OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report and National Statistical Offices/Ministry of Finance.

This article was written by Wilson R. Erumebor. All views are strictly that of the author and do not represent the views of any organisation he works for or is associated with.