Five reasons why Nigeria’s next economic recession will be worse than ever

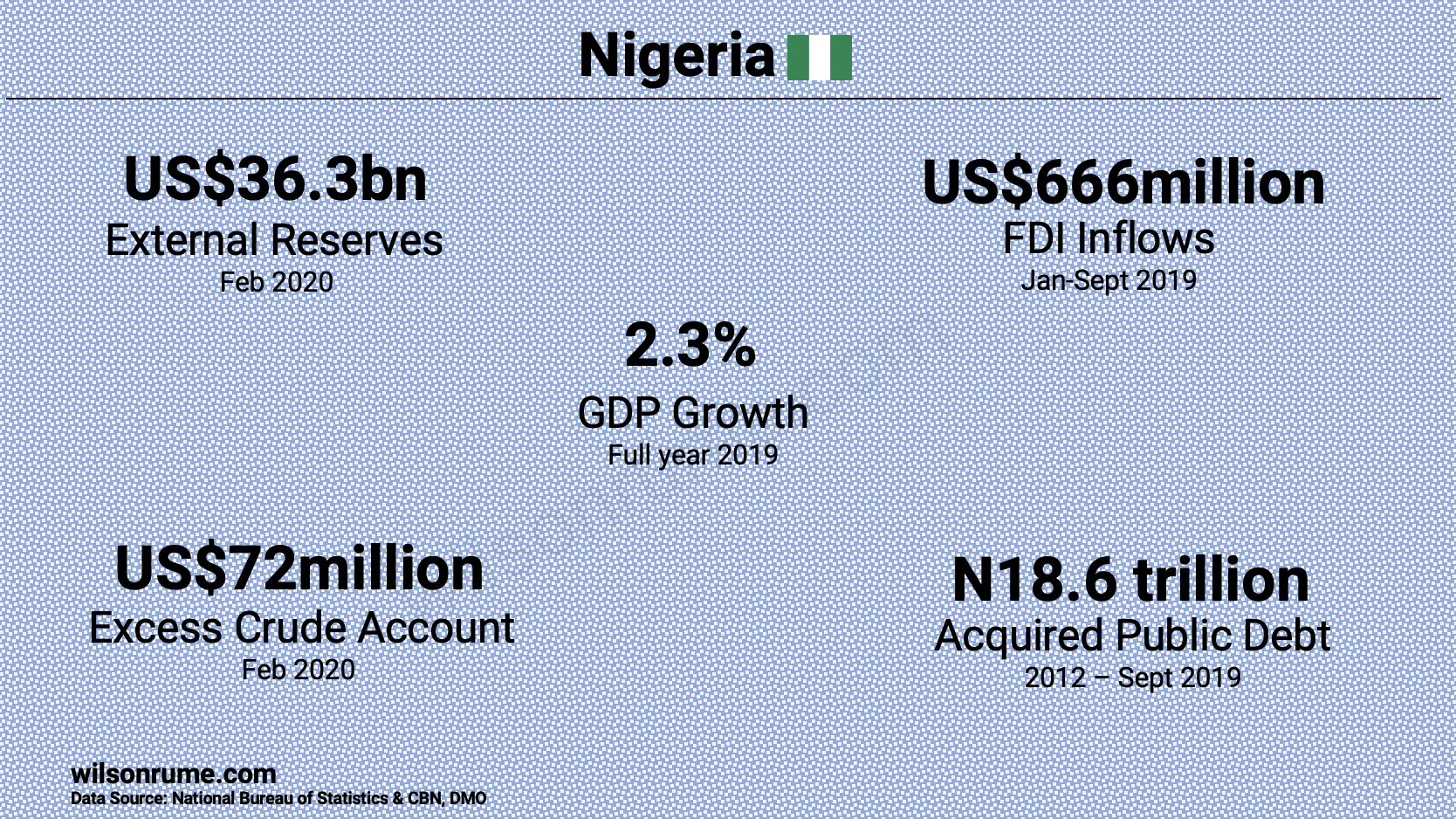

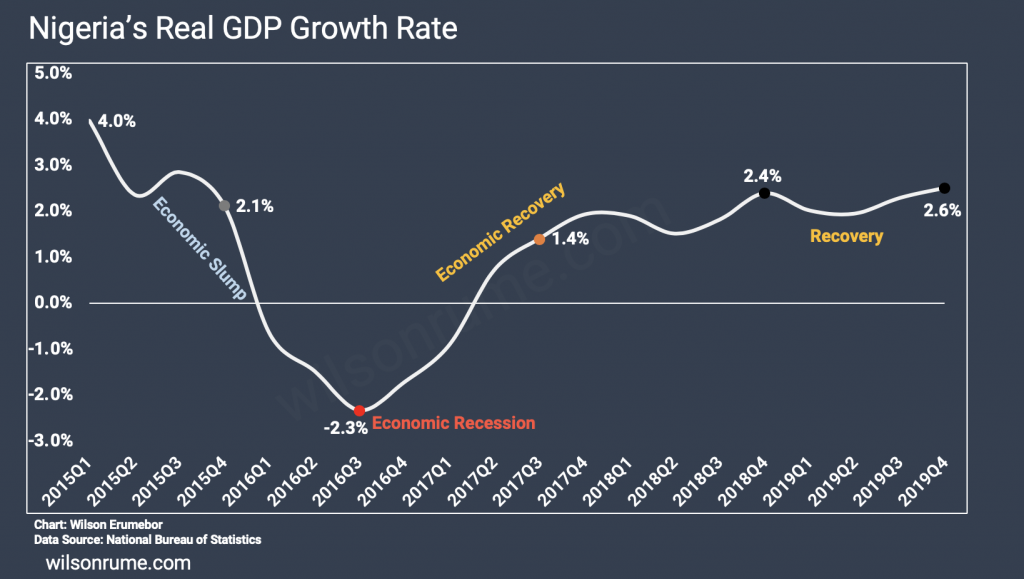

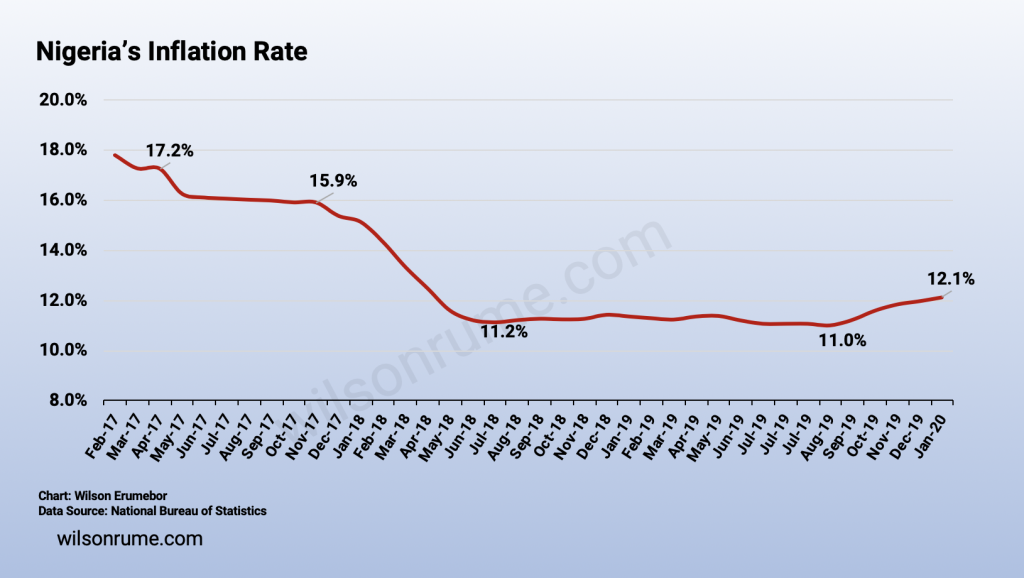

On Friday, February 28, 2020, Nigeria reported the first confirmed case of the Corona virus. Prior to this, Nigeria has been feeling the impact of the virus through declining crude oil prices in the international market. Oil price (Bonny light) declined from US$70 per barrel (pb) in January 2020 to US$50pb on February 28th, below the 2020 budget benchmark of US$57pb. With oil price as low as US$50 pb and a possibility of falling further, in addition to wavering oil production, the finances of the Nigerian government and the country’s exchange rate will be negatively impacted and this will spill over to the rest of the economy. Nigeria’s recent experience of an economic recession was in 2016/2017 when crude oil price fell significantly to US$26 pb in January 2016. As a result, external reserves fell to a low of US$24 billion in October 2016 while inflation reached an all-time high of 18.7% in January 2017. The recent drop in crude oil price as a result of the virus, if sustained, has a possibility of leading Nigeria into an economic recession by 2021. What is even worrisome is the weak macroeconomic fundamental which suggests that the next recession could be more fatal than the previous one.

Below are five reasons why the next economic recession will be worse than ever.

1. Nigeria does not have adequate external buffers

Many of the large oil producers usually have external buffers either in the form of external reserves or sovereign wealth fund to cushion the effect of falling crude oil price. Nigeria has an excess crude account (ECA) which was instituted by President Olusegun Obasanjo to save the excess oil revenues. Reports show that the ECA had a balance of US$20 billion in January 2009, which declined to US$9.5 billion in February 2013. As at February 2020, the balance in the ECA was US$72 million. This shows that within the last 10 years, a net amount of US$19.9 billion has been withdrawn from the ECA and shared among the different levels of government. Similarly, Nigeria’s sovereign wealth fund has remained at US$1.5bn, a meagre amount compared with that of Saudi Arabia (US$320 billion) and other oil producing countries.

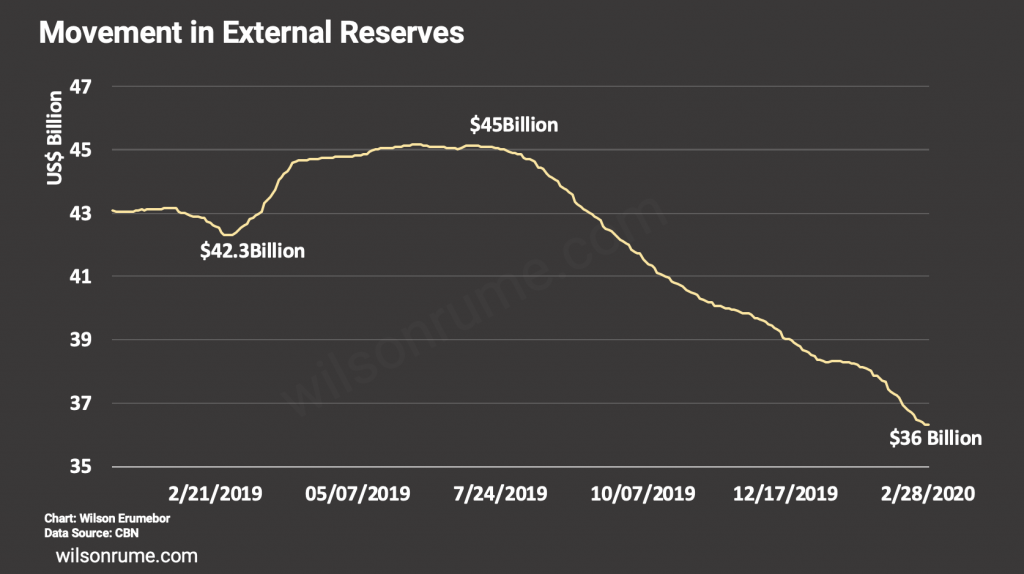

In addition, Nigeria’s external reserves have been on a free-fall since July 2019 despite higher and stable crude oil price in the second half of the year. Reserves opened 2019 at US$43 billion but rose to US$45 billion in July. Lower inflows of foreign investments, higher import demand and foreign exchange obligations led to a consistent and significant decline in reserves to US$36.3 billion at the end of February 2020. If Nigeria could not grow its reserves when oil prices were relatively higher, lower and declining oil price, therefore, would continue to add pressure on the reserves.

Earlier in 2019, the CBN governor was quoted in the media as saying that he would be worried when oil price fall below US$45pb and reserves fall below US$30 billion at the same time. If the Corona virus situation worsens, both scenarios are likely to play out by the end of 2020 or early 2021, thus, creating concerns regarding external reserves, exchange rate stability and other key economic indicators.

Clearly, Nigeria does not have adequate buffers to prepare for the rainy days which could be fast-approaching as oil price declines.

2. The environment is not FPI/FDI friendly

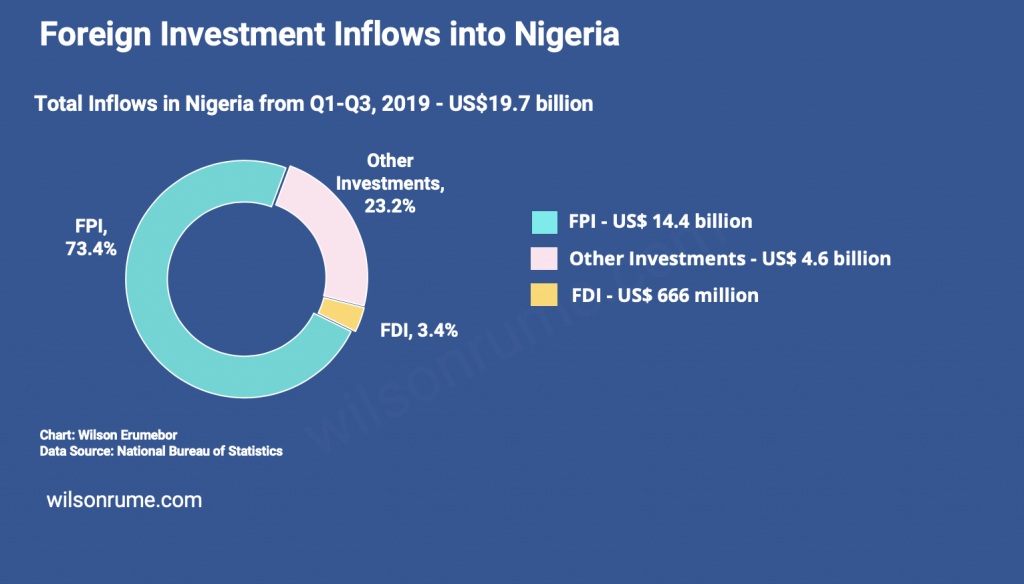

Foreign investment inflows consist of Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Other Investments. In the first nine months of 2019, total foreign investment inflows into Nigeria was US$19.7 billion and 73% of total inflows were FPIs. With an underperforming stock market, lower interest rates in the fixed income markets due to the impact of CBN OMO policy as well as uncertainty about the economy, FPI inflows in 2020 are set to be lower than what was recorded in 2019. So, the big question remains how can the Nigerian economy incentivise the inflow of FPIs at a time when interest rates are low and macroeconomic fundamentals are not doing well?

In relation to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Nigeria attracted US$666 million representing just 3.4% of total inflows in the first 9 months of 2019. Insights from past trends suggest that FDI inflows for the full year of 2019 will fall below US$1 billion, same figure that was recorded at the peak of the recession in 2016. Given Nigeria’s large markets, abundant human and natural resources and the potential that exists across different sectors, FDI inflows of US$1billion is significantly low. Countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia attract about US$30 billion and US$8 billion worth of FDI per annum, respectively. The fact that Nigeria cannot attract significant FDI three years after the recession sends a signal on the level of uncertainty, harsh business conditions and uncoordinated policies in the fiscal space. Despite some key milestones recorded by the Presidential Enabling Business Environment Council, doing business remains a challenge and Nigeria needs to implement tough and serious reforms to ease the business environment in order to attract significant inflows of FDIs into the country.

3. Higher and rising debt levels

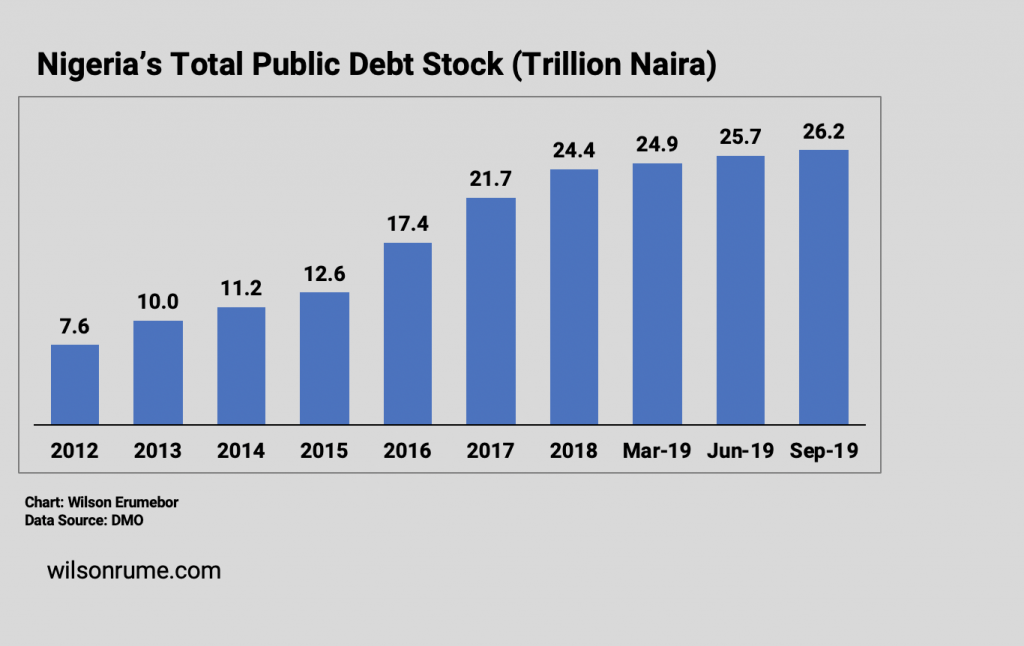

The third reason why the next recession will be tougher is the high level of public debt. Nigeria’s total public debt has more than tripled from N7.6 trillion in 2012 to N26.2 trillion in September 2019. In addition to rising debts is the higher debt servicing costs which account for about 45% of total revenue as at September 2019. With the lower oil price which only suggests that revenues will fall below budgetary targets, public debts are expected to continue to increase sharply and could reach N30 trillion by 2021. As the economy goes through hard times, additional debts will be used to finance payment of salaries and other recurrent expenditure items, while capital component of the budget will suffer. Nigeria could be trapped in a debt circle and debts could rise to unsustainable levels in the next few years. The country would also suffer downgrades from international rating agencies.

4. Weak resilience of the private sector

The formal private sector in Nigeria is not as firm as expected and this makes the overall economy highly vulnerable to shocks that directly affect the government. This point has two dimensions. The first looks at the direct relationship with or exposure to government activities. As experienced in 2016, the economic recession tested the resilience of the non-government economy and showed that any shock that affects government finances has a stronger linkage in affecting other aspects of the economy. This transmission happens through government contracts and procurement and the payment of salaries of government workers. Little wonder why across many of the 36 states, the economies of these states are subsistence based; rely heavily on government and therefore revolve around the state’s capital. As many state governments wait for FAAC allocations, so do businesses and other economic agents. Building the economic system around government means that whenever the government encounters trouble with its finances, other economic agents -such as households and businesses- suffer.

The second dimension relates to the fact that Nigeria’s non-oil economy does not export enough output to generate adequate foreign exchange, needed to sustain the economy. For instance, non-oil exports accounted for 13% of total export earnings in 2019. Therefore, reserves accretion and export earnings are significantly linked to crude oil price/exports, thereby increasing vulnerability of the economy to oil price shocks. Efforts are therefore required by the government to build economic resilience by attracting significant private investments into key sectors of the economy to boost outputs and exports.

5. Rising Inflation Rate

Inflation rate has risen significantly from 11% in August 2019 to 12.1% in January 2020, responding to the border closure. Food prices remain a key factor in the rising inflation. Further shocks to the economy, particularly from the external sector, could add further pressure on average prices through imported inflation and depreciating Naira as experienced in 2016. Drawing from Nigeria’s recent experience, rising prices typically has more negative effect on the poor especially when real income has not grown significantly in previous years.

In conclusion, the performance of the Nigerian economy depends on the movement of the price of a single commodity- crude oil. The Nigerian government needs to do more and be proactive rather than reactive in pursuing proper economic diversification, both in terms of government revenue and export earnings. The call for economic diversification is not new; and has been advocated for by both economists and non-economists since the 1980s. Obviously, as a country, we have not learnt a great deal from the last recession. Perhaps, the next economic recession will ensure the government implements some tough reforms to strengthen the resilience of the economy.

This article was written by Wilson Erumebor. All views are strictly that of the author and do not represent the views of any organisation he works for or is associated with.

Ifeoma Glory Solanke

This is scary Wilson. It doesn’t seem like it will get better, especially as we have leaders who do not seem perturbed about it.

This is an insightful piece. Disturbing but a truth worth knowing. Thank you for the wonderful effort.

Wilson Rume

Thank you Ifeoma Solanke.

Sodik Adejonwo Olofin

Nice piece I must say, I feel saddened the more about the situation as we do not see any policy movement in the right direction. This was reflected in the manner of closing the border.

Wilson Rume

It is sad reality. The more reason why we need to keep pushing and advocating for the right policies.

Agbo Manasseh

Great piece of information to keep in mind.

Wilson Rume

Thank you Agbo

Shina Ojo

Great work!

Thanks for the analysis

Wilson Rume

Thank you Shina..

olasunkanmi ige

Thanks for this information. its obvious that our sole reliance on oil production as brought us where we are today, not giving cognizance to the non- oil producing sector that can help us in situation like this if well invested in and more export from that sector could actually bail us out.

Good job.

Wilson Rume

You have summarised it all! Thank you for the comment.

Jeannetta

The article is very current for what we live, and

life is getting harder. I have made a way to have a real job at

home, without cheating, maybe it will help someone: https://bit.ly/2RbR38c

Lucky

nice

Gift Okiogbero

Very insightful & succinct. Thanks Wilson.

Wilson Rume

You’re welcome Gift.

David

Nice insights

Gladys O.

Bro, its so unfortunate that our policy makers do not see what is going to hit us soon. We need people like you to make and implement policies that will better the life of each Nigerian’s but greed will not allow us. What they know is now now, not thinking of the future.

And the over dependent of Oil is totally a big mess for us.

May God see us thru.

Wilson Rume

Valid points. Thank you for the comment Gladys.

Pingback:These 10 tips will help you survive the forthcoming recession – Wilson Erumebor